By: Hannah Anderson

Several years ago, I was lucky enough to teach the primary Sunday School class at a small brick church that was flanked by a running stream. The church was named after the brook and on years when Easter came in April, its waters would be dammed to make the Sea of Galilee for the annual Easter Pageant. The rest of the time the stream flowed simply, its boundaries marked by large oak and maple trees that grew along the bank.

One summer, inspired by our surroundings, I decided to spend several weeks teaching the children Psalm 1. Each Sunday, we’d take attendance and then tramp outside to where trees were literally “planted beside flowing streams.” We’d feel the rough bark of the oak and stand up with our backs against its broad trunk. We’d crane our necks and look up to the leafy canopy overhead, dizzy beneath its towering branches. We’d bend down and brush the dirt away from its roots and wonder aloud at how they could hold this miracle of a tree upright. And then we’d open our Bibles and learn how we could be just like this tree if we planted ourselves next to the waters of God. We’d talk about how we could soak up all the goodness of God’s life-giving stream and over time, grow tall and straight up toward heaven.

I realize that not everyone has the good fortune to worship beside a brook, but if my days at small brick church taught me anything, it’s the importance of combining what we learn about God inside the church building with what we learn about him outside it.

Like the adults around them, children today are increasingly detached from the natural world. According to a 2018 report by the CDC, children aged eight to ten spend an average of six hours a day in front of screens. Such habits have been linked to sleep deprivation, obesity, and delayed learning, but the risks go beyond the psychological and physiological. I contend that there are spiritual dangers as well. Or at the very least, we’re missing prime opportunities to disciple children through the witness of nature.

Psalm 19 tells us that God reveals himself through creation: “The heavens declare the glory of God, and the expanse proclaims the work of his hands.” Even though creation does not use words or have a voice (19:3), somehow it still proclaims a message that extends to the ends of the world (19:4). Theologians call this message “general revelation” because it is open and available to everyone. Unlike the written text of the Bible (or “specific revelation”), creation does not require reading skills—a point that I felt keenly in my primary Sunday School class. Instead the witness of creation is accessible to anyone who wants to hear it.

But what happens when we don’t spend time in creation?

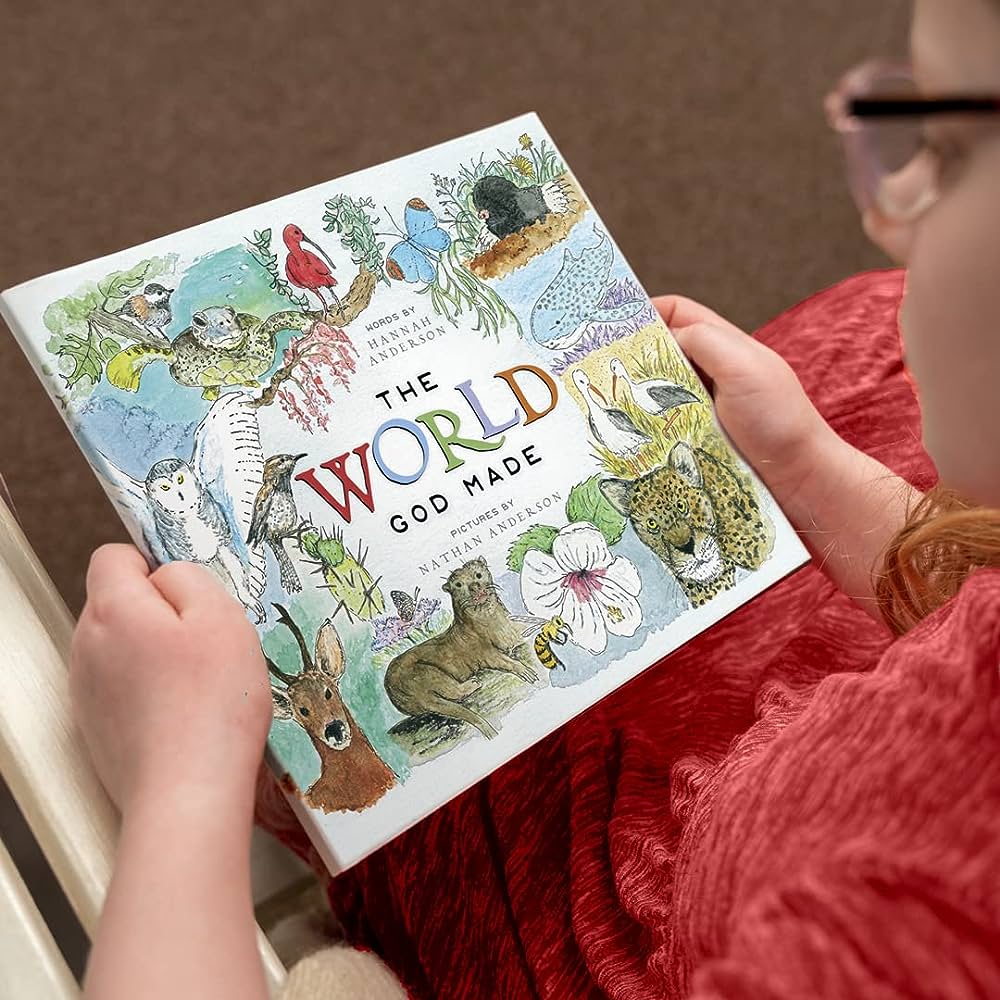

One of the first casualties is that we lose our understanding of the Creator’s majesty and glory. Whether it’s a bright red lady bug, a summer thunderstorm, or yes, a tall oak tree beside a flowing stream, nature invites us revel in wonder and awe in a way that human artifacts cannot. In this sense, creation invites us to a space beyond and outside ourselves, teaching us the goodness of not being the center of attention. It humbles us and shows us how to be small—how to find our place as part of the world God made. And most importantly, it teaches us that God is bigger than all of it.

Such encounters do not need to be complicated to cultivate wonder in children. Given the proper attention and attonement, the simplest things within God’s creation can open a door on worship. Writing about how children’s imaginations can be shaped through simplicity, author William Martin writes,

Show [children] the joy of tasting

William Martin

tomatoes, apples and pears.

Show them how to cry when pets and people die.

Show them the infinite pleasure

in the touch of a hand.

And make the ordinary come alive for them.

The extraordinary will take care of itself.

When we invite children into creation this way, we’re leading them to an embodied experience of God’s majesty so that when we do finally return to the classroom and pick up our Bibles and to read about the King of all the earth, we might just have a category for him. But if it’s true that “attitudes are caught and not taught,” then adults must be the first ones to step outside. We must find ways to incorporate nature into our conversations and curriculum. We must not forget what Psalm 19 says about the witness of the world around us. And as we step out, children will naturally follow us with eyes wide open. They’ll follow us and together we’ll discover the One who made the brook and tree and each of us as well.

The Great Commission Isn’t Just for Adults

The Great Commission Isn’t Just for Adults »

»